When you take out all the external trappings from modern marketing, it boils down to two basic things—understanding human psychology and using common sense. It’s what makes marketing easy and accessible for everyone.

Unfortunately, it also lowers the barrier for entry for everyone—which is why marketing sometimes becomes a channel for people who are looking for shortcuts and hacks to manipulate the masses.

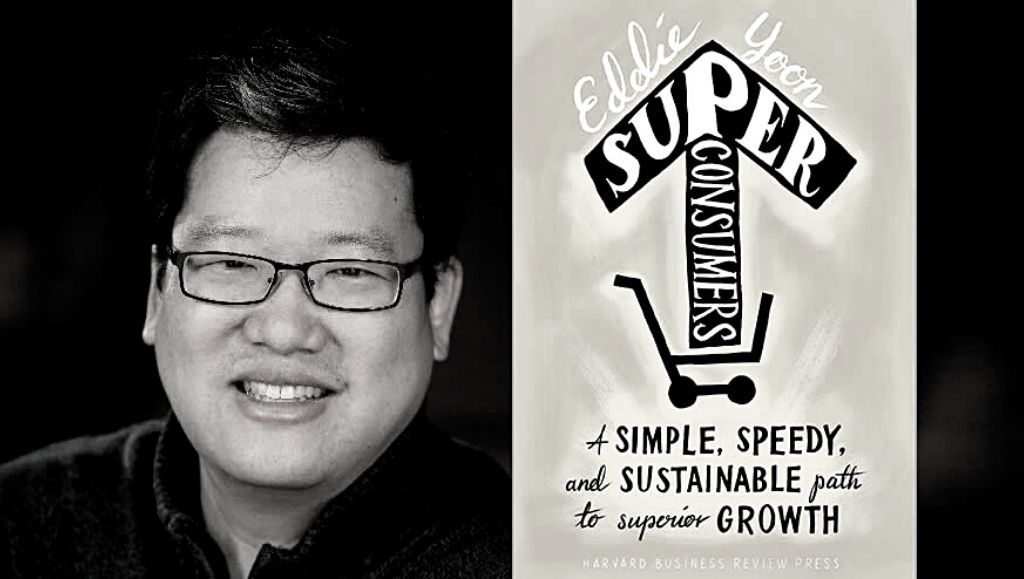

Seth Godin is one of the best marketing minds in our times who understands the predicament that modern marketing is going through right now. He recently appeared on The ABM Conversations Podcast to discuss the fundamentals of modern marketing.

Here are the excerpts from the show:

On marketing

In the modern marketing world, everyone hates marketing except for the marketing that works on them. Off late, there’s an enormous number of short-term, narcissistic, selfish, profit-maximizing people who are calling themselves modern marketing professionals, who aren’t marketers at all.

They are just hustlers that they call themselves “growth hackers” as if that’s something fancy. What they are doing is pushing something forward against the wishes of the people that they are marketing to. And that’s the stuff that we don’t call marketing.

It takes patience, insight, and empathy to deliver anticipated personal, and relevant messages to people who want to get them. Unfortunately, those three things seem to be in short supply these days.

As responsible marketers, we should create work that matters for people who care and choose to show up with stuff that people would miss.

On creating categories

I see category creation from the semantic standpoint. What is a category? Did Airbnb invent the category? I don’t think so. Did Facebook invent a category? Definitely not.

Besides the fact that it’s fun to say, “oh, those people succeeded because they invented a category,” it’s pretty clear that there’s only two categories—wants and needs. You can divide everything else within those categories into smaller and smaller slices.

The people who are talking about inventing a category, what they mean to say is you’re not a commodity—unless you act like one. And if you act like a commodity, then you’re doomed.

Differentiation is selfish, because it says, “I need to stand out. So I will invent artificial distinctions.” That’s the opposite of positioning—which is a service. It’s a service because buyers don’t have a lot of time. For example, if you have certain things you want to buy, you will go to one of the edges of what is on offer. When you decide you want something like that, it will be your obvious choice.

I like to talk about chocolate for this. Askinosie sources its dark chocolate ingredients from the Philippines and sells its bars for $20 each. They don’t compete with Hershey’s. Both brands make chocolates, but Sean Askinosie and his daughter Lauren didn’t differentiate Askinosie.

Instead, their marketing says that Askinosie is for adults who want to spend a lot of money, get more than they pay for, and who want a remarkable ethical thing. And that’s exactly what they make.

If you want a Hershey bar, Askinosie is eager to have you buy a Hershey bar. They are not going to try to stop you from buying a $2 Hershey chocolate bar because they are selling Askinosie for the other people.

On niching down

We marketers have been brainwashed into trying to serve the biggest possible audience. This is especially true if you work closely with the VC (venture capital) world—which is filled with a lot of people who don’t really understand what’s going on but they’ve been lucky with the thesis. A lot of times, the VCs tell the brands that they need to cross the chasm and sell to everyone.

The truth as Seth Godin says, is that there’s no such thing like selling to everyone. Even the best-selling authors in America reach only 2% of the audience. The biggest cable networks—the ones you would be happy to own—reach only 2–3% of the audience.

The brands that avoid niching down do so because they think their ideas are so good that everyone needs to buy it. But they’re fooling themselves because everyone doesn’t need to buy from them.

On the other hand, the brands that embrace niching sometimes get caught up in a niche because of the features that their products offer—not based on the dreams and desires of their customers. But that’s why people buy from you, particularly in the B2B space. Let’s be really clear about B2B.

The first thing is—most people buying a B2B product are not spending their own money. That’s a huge distinction.

The second thing is—if you are a commodity, you aren’t giving enough reason for your buyer to convince their boss in terms of your product being a must-have. For example, if you are answering RFPs, you are commoditizing yourself and not standing-out enough.

The third thing—which is the biggest thing—when someone buys from you in B2B, they’re only asking one question: what will I tell my boss? If you don’t give them a really good answer to that question, then they’re going to tell their bosses, “Boss, I got it for a little cheaper.”

As a brand, you have to give something better than that for your buyers to say to their bosses. Otherwise, they will probably buy the commodity because they are afraid to say something bigger than that to their boss.

Your goal shouldn’t be to niche down. You should be specific about who is the smallest viable audience for your product. Be specific about the dreams, needs, and wants of the person who buys from you. Be aware of the stories that they might tell others. Once you figure that out, the products you make will take care of themselves.

Seth Godin: finding your niche

Let me give you a specific example with my book—Purple Cow. When I finished writing the book, I had to self-publish it. I printed 5000 copies of the book and put them in milk cartons.

I then wrote about the book in my column in Fast Company. Back then, roughly about 90,000 people read Fast Company every month. So I said to these 90,000 people with permission, “Here’s an excerpt from my book. If you want a free copy, send me $5 for postage and handling, I only have 5,000 copies.”

That $5 covered my postage and my printing, so I was going to break even. When they mailed me the $5 postage, it demonstrated that they were early adopters of my book because of the 300 million people in the U.S., only 90,000 subscribed to Fast Company and read my column.

Out of that, only 5000 went through the trouble of mailing me $5 for a free book. When I finally shipped the book in milk cartons, I was doing something intentional, which is—the people who got the book put it on their desks. Why? Because they wanted their coworkers to see the milk carton. Because they wanted their coworkers to ask, “What’s a purple cow?”

That feeling is why they wanted the book because they liked being first. They liked being seen by their coworkers as early adopters—as people who lean into new ideas. By giving them a phrase that made them the smartest people in the room, by giving them the ammunition they needed to help their company make better work, I solved their problem. They weren’t solving my problem.

That’s the key to all of this. When you show up with a new software, a website, or a widget—it should solve their emotional problem, not their commodity problem. In return, they will say thank you and you don’t have to hustle.

But is it easy or difficult to find these people? How do you choose whom to bet on? Well, it’s an experiment. There will always be people who are going to react and certain people who are not going to react.

The thing is, you’re not looking for them—they’re looking for you. And the reason they’re looking for you is because they have a problem. So it’s your job to figure out where do these people with this problem go and go there. That is fundamentally different from the selfish mindset that most marketers use.

On developing a good marketing mindset

We need to own our work because if we don’t—who will? I am a teacher, but I’m also a game designer. I started designing games in 1976 on the internet and built one of the most popular online games of the Prodigy/AOL era.

I think about the world in terms of games and games don’t force people to play. Instead, they seek enrollment. Games start by asking—who is enrolled in this journey? Who wants to go somewhere else? Who’s willing to play this game with me? What rules are permissible in this game?

To pick an example that people are familiar with—TED Talk is a game. It’s a game because only 3000 people get into the final round in Vancouver. It’s a game because only 100 people get to go onstage and give a speech. Ultimately, it’s a game of status. You can go down the list of all the interactions that are wired around status and affiliation from selecting speakers, all the way to the TED Talk video that reaches 50 million people.

We’re all playing that game. It doesn’t put food on our table. It’s simply fun and engaging. It makes us glad that we did it. And most of the things that we make and sell at some level is a game.

The people who are looking for hacks will tell you that they are playing long-term games, but all they are doing is keeping track of their exits and revenue. They are not keeping track of return customers. They’re not keeping track of opportunities created. They tend to work in the shadows. They are afraid that if they published all of their insights, people would either steal them or shun them.

But the people who are in it for the long haul give away everything they know because the infinite game gets better when other people know the rules.

On failing fast, tactics, and strategies

There are a couple of pieces to it.

The first is—if you take a bunch of raw dough and put some cheese on it, you don’t want to test whether people like it or not because it’s not yet a pizza. You have to bake it before you get people to like it.

The minimum viable product has to have a minimum threshold. It has to be something that people can use. But that doesn’t mean you have to push it to be perfect. It just means don’t ship junk.

The second thing is—there’s a difference between strategy and tactics. Tactics are based on what your competition is doing. Tactics keep changing and you have to keep them a secret. But you can publish your strategy in public. You have to stick with it for a long time.

I met Guy Kawasaki and worked with him briefly in 1983. It’s miraculous to find Guy and I mentioned in the same sentence 38 years later. Just before the Mac came out, Guy delivered one of the first Mac computers to me to use it as a beta tester. Thirty-seven years later, Apple still has the same strategy in its business. They haven’t changed their strategies because you stick with them.

You shift the tactics all the time because they have to change. But once you commit to serving your minimum viable audience and you know what they need, want, and dream of—don’t change that. Commit to it for a long time.

On mistakes, blunders, and experiments

Mistakes are tactics that didn’t work, but that taught you something. Blunders our moral failings or sloppiness that gets you kicked out of the game. There’s a fine line between the two and it’s helpful to know the difference.

I wrote a book called The Dip that talks about when to quit or when to stick with an idea. I used to be one of the most important DVD producers in the U.S. But I’m glad I don’t do that anymore because no one buys them. I used to make online games. I don’t do that anymore either. I used to run Akimbo (Seth Godin’s podcast that has been rebranded into a learning platform for all kinds of professionals)—but I don’t do that anymore.

To grow is to acknowledge that there are sunk costs in your life and to realize that there is a choice on your part, whether you carry them around or not anymore. If you can’t serve your audience by sticking with what you are, it’s okay to move on and do something else.

On following your passion

It is much more resilient to be passionate about what you do than trying to guess what you would be passionate about and go after that. If you choose to be passionate about what you are already doing, then you are almost always going to be in the right place—at least until you decide to be someplace else.

On brand promise

A brand is not a logo. A brand is a promise. It is an expectation. It is a shortcut.

Patagonia makes difficult-to-make parts for people who do aggressive mountain climbing. When Patagonia came up with their first jacket, the mountain climbers knew what to expect from a Patagonia jacket. Patagonia figured out that they could also make luggages because as long as the luggage is for a similar group of people and works in a similar high-performance way, the brand is intact.

On the other hand, Yeti makes coolers. The Yeti cooler led to the Yeti tumbler. The Yeti tumbler worked out because they actually made a tumbler that was much better than regular tumblers, the same way a Yeti cooler was much better than regular coolers. But now Yeti wants to make luggages. And I, as somebody who has encountered yet, am skeptical that they can keep the brand promise that they can make luggage that is much better than regular luggage the same way Yeti coolers are better than regular coolers. That’s where brands get in trouble.

Your brand should stand for something—usually an emotion. If you can bring that emotion for the same customer or to a different place than you can do well with it.

If I had to talk about Apple as an example here, it was a company that was originally known for computers until they started making iPods, iPhones, and AirPods. So how do you look at that? What does Apple stand for? It has changed in the profit-maximizing Tim Cook-era, but it is still similar to what Apple is largely stood for, i.e.—good taste in digital experiences.

People who see themselves as having good tastes, people who want to be seen by others as having the status that comes from having good tastes are drawn to the luxury goods that Apple makes. Apple’s products stopped being more productive or more efficient for the dollar a long time ago. But they still bring with them the expectation that you have good taste and high status because of the attention to detail that goes into making Apple products.

The challenge that Apple has today, because Tim is trying to maximize profit for the company, is that they have forgotten to take care of many of the rough edges in their products. For example, the Keynote is not a better piece of software than it was five years ago. Keynote doesn’t make its users seem any better than a PowerPoint user—the way it did five years ago.

As a brand, Apple has a lot of work to do if it wants to get bigger again because of its brand promise. The amount of competition they have is so significant that they will have to do some bold things to keep that promise in the future instead of just doing the things that get them profits.

On 30-foot rule

Let’s say that you come out with a new line of snack food in the supermarket business. If I—as a consumer—can’t tell from two miles away that that’s the one you made, then it’s not distinctive. It’s just a me-too brand.

<embed: https://twitter.com/ThisIsSethsBlog/status/1377917522670972932?s=20>

But the point isn’t just about being distinctive. It is about putting your signature to your work—whether it’s a website you design, the way you speak in a microphone, show up in a Zoom call, or participate in meetings. Can we tell that it is you, is it consistent and distinctive in service of the people that you were there to work with?

If it’s not, then you have chosen to be indistinguishable.

On the future of audio social

There’s no dispute on how Clubhouse launched technology to the cool kids better and with more heat than almost any organization I can think of. They became a certain kind of digital hipster in the shortest period of time. However, there are some fundamental flaws of efficient interaction in the whole idea of audio social media.

Problem #1 is—it doesn’t scale and that it doesn’t have any asynchronicity to it. It demands that you find something worth listening to or participating in every time you log on—which is hard to guarantee.

Meanwhile, almost everything else on the internet is asynchronous. You can watch the Low Darts’ song performance that they recorded two weeks ago on YouTube. You can read a blog I wrote eight years ago.

Problem #2—you can’t really search for anything specific on audio social media because it’s audio. So if it’s live and you can’t search it, it’s even harder to surface and find.

Problem #3—it’s not a natural monopoly. Why should there be only one channel for this? It makes perfect sense that there will be many other players. It’s likely to become a commodified service so that a community of any kind—whether it’s Slack, Facebook or Discord—can install a plugin that gives them Clubhouse-like functionality.

And then there problem #4. Some things naturally monetize themselves such as search. When you do a search on the Internet, for example, you want there to be search ads because ads are a way of signaling that someone thinks it’s worth clicking. But you don’t want there to be ads on Clubhouse. The idea of linear audio makes it almost impossible to run effective ads—particularly direct marketing ads—because either it’s going to interrupt the flow of what I’m doing. I would either hate them or skip them, in which case they don’t matter.

Seth Godin said “I have been in the media industry for 40 years now and there isn’t a lot about this medium that strikes me as a business or something that will change the culture in significant ways. It strikes me more as some growth hackers, flexing their muscles, combined with the cool kids, making it the thing of the moment. But I’ve been wrong before. So I don’t know.”

On who should own storytelling within a company

Just like how accounting is anything that touches the accounts, marketing is anything that touches the market. And the modern marketing aspect that touches the market the most is the story your company lives and breathes.

It’s things like who you hire, what you dump in the river, what your pricing is, how you answer the phone—all of that is marketing. That has to go all the way to the top. It begins with the people who deal with customers and it ends with people who sign the paycheck. And if those people aren’t in charge of marketing—who else is? If they are in charge of marketing, then they must be clear about what they stand for and don’t stand for. But if your company thinks you can pick anyone and everyone to tell stories, then you’re doomed.

On solving customer problems

I wrote about this in “This Is Marketing.” People only care about two things—affiliation and social status. Once people meet their basic needs, all they care about is affiliation and status. Affiliation is when people look for other people who are like them and try to be affiliated with like-minded groups. Status is when they ask themselves—will this make me better than my peers? Will this keep me from falling behind?

Think about a car commercial that brags about how much horsepower it offers. You know that you are not going to be in a race with anyone—you don’t need to know about the horsepower. What the commercial is actually saying is—this will make you cooler than your next door neighbor.

This is Facebook’s entire strategy. Their messaging tells you, “people are talking about you behind your back. Do you want to hear what they’re saying?” It’s the same with LinkedIn who say, “there’s a big club going on and you are not in it. You better catch up!”

So we keep coming back to those two things—status and affiliation. As copywriters, strategy makers, and storytellers—we need to ask each other the following questions before we spend a nickel on advertising, marketing, or sales:

- Who’s it for?

- What’s it for?

- What are we promising when it comes to affiliation?

- What are we promising when it comes to status?

If you can’t figure that out, you should probably go home and not come back until you can.